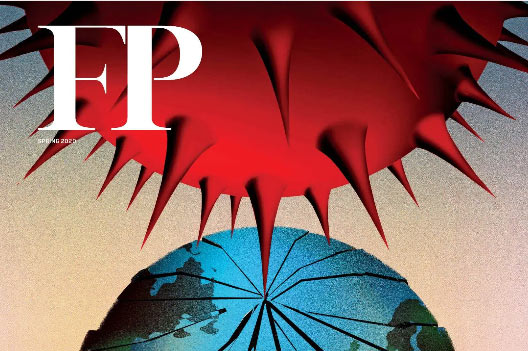

The Ugly End of Chimerica

Washington’s policy of engagement toward Beijing has been embraced, with a few bumps along the way, by eight successive U.S. presidents—an incredible record of continuity. The approach was born in 1972, when the fervently anti-communist President Richard Nixon and his national security advisor, Henry Kissinger, set off for Beijing to make a game-changing proposal: The United States and China should end their decades-long hostility by allying against the Soviet Union. As Nixon declared to Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai, whose hand former U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles had refused to shake at a Geneva conference in 1954, “If our two people are enemies, the future of this world we share together is dark indeed.” He went on to insist that the two countries had “common interests” that transcended their differences and that “while we cannot close the gulf between us, we can try to bridge it so that we may be able to talk across it.” He ended grandiloquently: “The world watches … to see what we will do.”

The world is watching again, but most are expecting a very different outcome. Two giant powers that once seemed to be moving closer together are now tearing themselves away from each other—propelled by both politics and the impact of the global spread of the coronavirus. Decoupling was already underway, pushed by both Chinese President Xi Jinping’s rigid ideology and U.S. President Donald Trump’s nationalism. But as each country tries to blame the other for the coronavirus crisis, as the world becomes starkly aware of supply chains and their vulnerability, and as the global order shifts tectonically, China and the United States are moving further and further apart.

Until Trump came to power, the world took Washington’s lead by expanding cooperation with China, especially in the years following Mao Zedong’s death in 1976, when Deng Xiaoping committed his country to a bold new agenda of “reform and opening to the outside world.” Advocates of engagement hoped that this new policy would goad China into aligning itself with the existing liberal democratic rules-based world order so that over time it would also become more convergent with the interests of the United States.

Convinced of the seductive power of democracy and lulled by the promise of a seemingly ineluctable historical arc that bent toward greater openness, freedom, and justice, Americans tended to view the prospect of such convergence as almost inevitable. After all, if China wanted to participate fully in the global marketplace, it had no choice but to play by the existing rules—and after the end of the Cold War, that meant America’s rules. So certain did the likelihood of greater convergence seem that there was even talk of a so-called “Chimerica” or forming a “Group of Two.” These promises of a less contentious future allowed differences between China’s values and political systems and those of the democratic world to be downplayed. Proponents of engagement with China emphasized its future evolution under the tonic effects of its putative economic reforms and cautioned that a tougher U.S. policy would only harm the country’s reformers.

A remarkable consensus began to form on the topic of U.S.-China cooperation, one that transcended ideological boundaries within the United States. In 1979, President Jimmy Carter, described as America’s first “human rights president,” ignored China’s manifold rights abuses and not only welcomed Deng to the White House but restored formal diplomatic relations with great fanfare. In 1989, President George H.W. Bush bent over backward to preserve friendly relations after the Tiananmen Square massacre by twice dispatching National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft to Beijing to beseech Deng not to let the hard-won U.S.-China relationship languish.

When the Soviet Union imploded in 1991 and engagement needed another rationale, President Bill Clinton galloped into the breech. After promising not to “coddle tyrants, from Baghdad to Beijing,” and chastising his predecessor for conducting

“business as usual with those who murdered freedom in Tiananmen Square,” he ended up embracing Chinese President Jiang Zemin, lobbying to extend “most favored nation” status to Beijing, and even helping to usher it into the World Trade Organization. Clinton was the first U.S. president to name this new policy “comprehensive engagement.” His hope was that once China got the needle of capitalism in its arm, democracy would follow.

But China derived the largest benefit: Engagement neutralized the United States as an adversary at a time when it was most beneficial to Beijing.

President Barack Obama continued to pursue this promise, trying to breathe new life into the relationship by having Secretary of State Hillary Clinton reassure Beijing that his administration would not allow sensitive questions like human rights to interfere with cooperation on climate change and economic crisis.

U.S. corporations and consumers both profited from these policies, even as the country was forced to compromise some of its democratic principles and tolerate a growing trade deficit. But China derived the largest benefit: Engagement neutralized the United States as an adversary at a time when it was most beneficial to Beijing. During those 30-plus years, China emerged out of its revolutionary cocoon, developed its fragile economy, laid down its modern infrastructure, and became an important part of global institutions. In a sheltered environment, one in which it was relieved of the threat of war with another big power or even serious hostility, China not only survived but thrived.

With Xi’s 2012 enthronement, however, the chemistry of this critical bilateral relationship began to change. Xi replaced his predecessor’s slogan of “peaceful rise” with his more belligerent “China Dream” and “China rejuvenation.” These ideas laid out a grand vision of a far more assertive and influential Chinese government at home and abroad. But Xi’s implacable assertiveness in foreign policy and his expanding domestic authoritarianism soon began alienating the United States as well as many other lesser trade partners, which found themselves caught in increasingly unequal, and sometimes even abusive, relationships they could not afford to vacate.

Xi’s ambitious new vision of a more aggressive and less repentant China produced a host of reckless policies: He occupied and then militarized the South China Sea; turned a generation of Hong Kongers against Beijing by gratuitously eroding the high level of autonomy they had been promised in 1997; antagonized Japan over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands, which the country had long administered in the East China Sea; rattled sabers at Taiwan so artlessly he alienated even the once reliably pro-Beijing Kuomintang party; and essentially turned Xinjiang into a giant detention camp.

The result has been not only tenser diplomatic relations with Washington, a trade war, and a decoupling of elements of the two powers’ economies but a dangerous fraying of the fabric of transnational civil society cooperation and even a disruption of cultural exchanges. Put together, Xi provided Washington with all the ammunition it needed to reformulate its once forgiving stance. The result has been a far more unaccommodating official posture supported by one of the most unanticipated coalitions in U.S. politics: a united congressional front of Republicans and Democrats who agree on little else. Without the catalytic element of Chinese political reform still in the mix, it is hard to imagine a Sino-American convergence regaining credibility anytime soon in the United States. And with divergence replacing convergence, engagement makes no sense.

Xi’s initial inability to manage the crisis has undermined both his air of personal invincibility and the most important wellspring of the Chinese Communist Party’s political legitimacy—namely, economic growth.

But what was Xi’s logic in implementing policies that rendered engagement so unworkable when they were working so well? What moved him to so alienate the United States when he did not need to? There are, of course, myriad specific rationales, but Xi has never articulated an overarching explanation that speaks to China’s actual national self-interest. The most plausible might be the simplest: Muscular nationalism and overt projections of power often play well at home among those ginned up on national pride.

But such indulgences are a luxury that can end up being costly in times of crisis. And the unexpected arrival of the coronavirus pandemic has been just such a moment. Xi’s initial inability to manage the crisis has undermined both his air of personal invincibility and the most important wellspring of the Chinese Communist Party’s political legitimacy—namely, economic growth. The initial numbers out of China for the January-February period show a 20.5 percent drop in consumption and a 13.5 percent drop in manufacturing year on year. Even as the country struggles back to its feet, markets in the rest of the world are going into lockdown.

Despite Chinese efforts to reclaim the crisis as a global propaganda victory—aided by the botched handling of the outbreak in the United States—the domestic blow dealt may be a mortal one, not to the party-state regime but to Xi himself, who has staked his credibility on the handling of the crisis. Unfortunately, the pandemic may also end up being the final coup de grâce of the relatively stable relationship China once enjoyed with the United States.

The Obama administration had already started reappraising the wisdom of trying to unilaterally keep engagement functional when along came Trump and his posse of China hawks (such as Peter Navarro, Steve Bannon, and Michael Pillsbury) who had long warned that an increasingly aggressive, autocratic, and well-armed China was both inevitable and a threat to U.S. national interests.

Then, just as a debate over decoupling from China’s supply chains got rolling, the coronavirus reared its head. As airlines canceled flights, trade shows were postponed, tourism screeched to a halt, investment flows dried up, exports and imports plummeted, and high-tech exchanges were truncated, the debate was ripped out of the hands of policy wonks and thrust into the hands of the gods. By decoupling the United States and China almost overnight, the pandemic has mooted the debate and provided Trump and his hawks with exactly the kind of cosmic sanction they needed to put a final stake through the heart of engagement—and perhaps even the whole notion of globalization as a positive force.

Yet most Americans continue to want globalization of some form—but perhaps with China playing far less of a dominant role. Now that U.S. businesses have turned skeptical of the old style of engagement, that policy has lost its last boosters. Even before the coronavirus crisis, companies made more aware of the risk of having all their eggs in one basket by the trade war were diversifying manufacturing away from China and toward other developing economies like Vietnam. The pandemic may only accelerate that process.

Source: https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/04/03/chimerica-ugly-end-coronavirus-china-us-trade-relations/