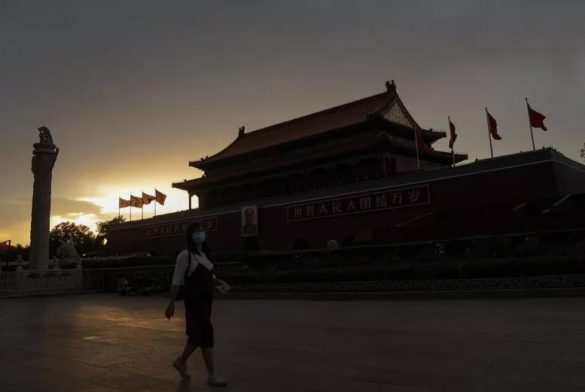

How China’s Hawks Still Exploit the 1989 Tiananmen Protests | Opinion

MICHAEL PILLSBURY , SENIOR FELLOW AND DIRECTOR FOR CHINESE STRATEGY, HUDSON INSTITUTE

In his Friday address on Hong Kong, President Donald Trump mused that we once hoped that “Hong Kong would be a glimpse of China’s future.” What he meant was that, for years, the consensus was that the Chinese government would evolve to resemble Hong Kong’s: democratic, protective of civil liberties, with a free market. Hong Kong was protected by a 1984 treaty between China and Britain, valid until 2047, by which time China would be just like Hong Kong. Trump accused China of violating this treaty, while China now even denies the treaty’s validity.

On the 31st anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre, it is worth taking a closer look at how China’s hardliners exploited that event to oust reformers who had been sympathetic to the demonstrators. How did these hawks use Tiananmen to transform China’s relations with America by blaming Washington, rewriting history and demonizing political opposition?

In 1989, the American foreign policy establishment agreed China was on the inevitable path to reform. It was a surprise, then, when 50,000 students marched in a Beijing memorial service for a former Communist Party head, who had been deposed by then-“paramount leader” Deng Xiaoping. For seven weeks, the students were joined in Tiananmen Square by approximately a million protestors demanding free speech, a free press and government accountability. They held copies of the Declaration of Independence and built a “Goddess of Democracy.” In the preceding few years, a few of China’s reform-minded leaders had begun to consider moving toward democracy, while hardliners organized to block them.

In late April 1989, I visited Beijing as a government analyst. Our acting ambassador, Peter Tomsen, invited me to drive to the square. No one obstructed our way as we approached a large cluster of students sporting T-shirts and long hair.

I spoke with them in Mandarin about my days as student protestor at Stanford and Columbia. A future legend who would receive the Nobel Peace Prize quickly introduced himself. He was wearing aviators and chain smoking. His name was Liu Xiaobo, of Beijing Normal University. He said that a few weeks earlier, he had been a visiting scholar at Columbia and had just flown to Beijing from New York to join the demonstrators. He would not really enter history for another 20 years, when he was imprisoned for signing the Charter 08 and advocating democracy. He received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010, but China refused to let him attend and even punished Norway for hosting a ceremony without him. His translated works prophetically warned of the rise of China’s hawks, called the ying pai. At that time in 1989, the mainstream view in the West was that these hawks would not prevail, nor would they ever use force against the students. No one imagined they would spread a powerful and false narrative.

But in May, these hawks persuaded Deng to declare martial law and rush 250,000 troops into Beijing. When the protesters refused to disperse, Deng sent in his tanks and soldiers. Hundreds of unarmed students died in the streets. Whole buildings were raked with gunfire. Soldiers kicked and clubbed protesters; tank treads rolled over their legs and backs. A lone man stood in the path of a row of tanks in the massacre’s iconic image. He was pulled away by a group of people—never to be heard from again.

After Tiananmen, many of China’s reformers (including the head of the Communist Party himself) were condemned to lifelong house arrest, while a few fled to the West to set up an exile government in Paris whose elected leader (Yan Jiaqi) had been a demonstrator and head of a prestigious research institute that had studied how to bring democracy to China. Government censorship increased—with a particular emphasis on purging the protest from Chinese news and history books. Within a year of the massacre, the Chinese government “had closed 12 percent of all newspapers, 13 percent of social science periodicals and 76 percent of China’s 534 publishing companies,” according to Minxin Pei’s From Reform to Revolution.

Though unclear to American officials at the time, June 4, 1989 was a turning point in how Chinese Communist Party leaders portrayed the United States to their internal audience. While there had always been a deep-rooted suspicion of the West within the Communist Party, it had been tempered by Mao’s calculation that China needed the West to become a superpower. Defectors later revealed that democratic reforms, even separation of powers, had been considered at the Party’s highest levels. By 2001, official documents smuggled out of China revealed how the hawks had distorted what was going on around Tiananmen to panic Deng into cracking down and dooming the reforms.

One thesis of my book, The Hundred-Year Marathon, is that these hawks have successfully persuaded the Chinese leadership to view America as a dangerous hegemon that China must replace. This view gained authority after 1989, and Beijing started systematically to demonize the U.S. government to the Chinese people. The hawks’ cry is straightforward: They claim the U.S. is overthrowing China’s government by sponsoring reformers, in part through non-government organizations.

China’s hawks were spooked by the Tiananmen protest and further frightened by the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991. America’s victory in the Cold War and the outright dissolution of the USSR shook Beijing. It underscored to Chinese leaders the hawks’ anti-American conspiracy theories. In their telling, Tiananmen was America’s first secret maneuver in its campaign to “sow discord in the enemy camp,” to borrow an axiom from the Warring States period 2,500 years ago. To these radical nationalists, the United States had almost succeeded in toppling the Communist Party, and was stopped only via a last-minute purge of American “allies” from the government.

The purge of pro-American reformers in China left few reform advocates in positions of power. The ravings of China’s hawks, once dismissed as “hyper nationalists,” became official Party doctrine in the Patriotic Education Law in 1994, which China later tried to impose on Hong Kong.

The Chinese government created an extensive “alternate history” of Sino-American relations, which portrayed a devious United States, continually working to undermine the Chinese people—even as, in reality, a series of classified American presidential directives set the goal to strengthen China’s economy for two decades.

Now, an emerging generation of Chinese believes this false narrative about the United States—that for 170 years, America has tried to dominate China. China depicts American national heroes as “evil masterminds” who manipulated Chinese officials and others to weaken China. We must never cease to remind ourselves that this is a lie. Today’s Chinese hawks must not be permitted to slander and defame the one million Tiananmen protestors’ honest efforts to reform China. Retelling the truth about Tiananmen every June 4 means opposing the hawks who so craftily rewrote reality as an American conspiracy.

What was the aftermath? The young professor Liu Xiaobo died in prison in July 2017, never having seen his Nobel Peace Prize, but leaving us his book, No Enemies, No Hatred. The first elected president of the exile government, Yan Jiaqi, now 77, lives near Washington, D.C. in obscurity. No nation ever funded Mr. Yan’s Federation for a Democratic China. His detailed history Turbulent Decade: A History of the Cultural Revolution, describing reckless Chinese Communist Party behavior from 1966 to 1976, is still widely read.

What about the hawks of Tiananmen? The leader of the crackdown, Mr. Li Peng became China’s premier. The most famous young hawk, Wang Huning, soon wrote America Against America, a book based on visiting 20 American universities. It initiated the anti-American movement in China. Today, Mr. Wang is the second most powerful leader in China, seated next to Xi Jinping on foreign trips. Mr. Wang was the sole leader to accompany Mr. Xi on his recent visit to Wuhan. Amnesia in China about Tiananmen in 1989 has combined with the rise of Mr. Wang’s nationalist anti-U.S. views.

Reformers in China who know all this history must be keeping their heads down, secretly watching Hong Kong’s annual massive vigil on June 4 to commemorate.

Michael Pillsbury, senior fellow and director for Chinese strategy at Hudson Institute, is the author of The Hundred-Year Marathon: China’s Secret Strategy to Replace America as the Global Superpower.

The views expressed in this article are the writer’s own.

Source: https://www.newsweek.com/how-chinas-hawks-still-exploit-1989-tiananmen-protests-opinion-1507718